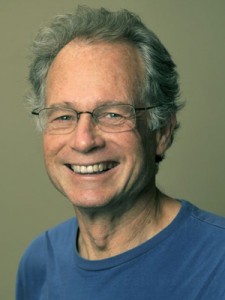

Former Wimbledon quarterfinalist Dan Goldie plays at Santa Barbara Tennis Club last week in a return to competitive tennis. (Paul Wellman Photo)

If you wanted to see an American tennis player in the Wimbledon men’s singles quarterfinals, you would have been out of luck at the All-England Club this year. But at the Santa Barbara Tennis Club (SBTC), the appearance of Dan Goldie was a throwback to the days U.S. men populated the late rounds.

Goldie, a quarterfinalist at Wimbledon in 1989, limped away from the pro tour 25 years ago with stress-fractured shins. He did not pick up a racket again until last fall to play in a charity event at Stanford, his alma mater. He began practicing against college players, and last week he returned to competitive tennis at the Ted Smyth USTA National Men’s 50 Hard Court Championships, the SBTC’s premier event for 15 years.

Fit and energized at 51, Goldie was a boy among men. He claimed titles in both singles and doubles, playing nine matches without losing a set. The singles final was a 6-1, 6-2 rout of Ventura’s Thomas Kong. Goldie and Mark Wooldridge, a Santa Barbara native, prevailed over Jeffrey Burnett of North Palm Beach (FL) and Mitchell Perkins of Seattle in the doubles final, 6-3, 6-2.

.

John Zant’s column appears

each week in the

Santa Barbara Independent

Goldie, a Palo Alto financial advisor, called the reception of Santa Barbara fans “a warm welcome back to tennis for me.” He recalled his days as a pro, when the competition at home and abroad was hot. He upset Jimmy Connors in the second round at Wimbledon in 1989 and was one of four U.S. men to reach the quarterfinals, where he lost to Ivan Lendl. John McEnroe was the highest-seeded American at the time. Goldie would play rising stars Pete Sampras and Andre Agassi before he was through.

Goldie came into tennis as a natural athlete who also played basketball, football, and soccer. “Every sport develops different parts of the body and the brain,” he said. “I met a coach who thought I could be good at tennis. I was almost 13 when I started playing in tournaments. I had to catch up.” Blessed with a strong 6’2” body, he became good enough to earn a scholarship to Stanford.

During his long absence from tennis, Goldie remained physically active. “I played 15 years of recreational soccer,” he said. “The grass didn’t hurt my shins.” Now that he has made a healthy return to the courts, he is ready to see if tennis can be his lifetime sport.

Wooldridge, who went from a championship team at Santa Barbara High to play No. 2 singles at Cal and spend four years on the pro tour, has made a nice transition to over-50 tennis. A Manhattan Beach resident, he sticks to doubles and has won the last three championships at the Ted Smyth tournament with three different partners.

Larry Mousouris, the tournament director and a fixture at the Santa Barbara Tennis Club for 42 years, was gratified to see Wooldridge and other players that he once coached still enjoying the game. But he is concerned about the spotty showings of U.S. men in primetime tennis.

In a culture where “everybody gets a ribbon,” Mousouris observed, the incentive to become the best appears to have waned. He noted the demise of a regional points system that used to stir up competition. “Now you have to have the money to fly around to build a national ranking,” he said. Prestigious tennis academies also suck up the dollars. In a system where everybody tends to take the same approach, Mousouris sees an overabundance of “cookie-cutter players.”

Goldie was impressed by the speed and power of the college players he’s gone up against. “They hit balls so much harder,” he said. But few of them make an impact in the international game. Wooldridge theorized that “there are so many athletes in the U.S.… nobody learns what it takes to be a champion. They beat each other up and don’t get to really believe in themselves.”

U.S. women’s tennis does not suffer in a similar fashion, not with Serena Williams slamming away and such players as Madison Keys on their way up. “A woman in tennis — you’re a rock star,” Mousouris said. “Men have football, basketball, and baseball.” But if you’re over 50 and still have the legs to run and the arm to swing, tennis is a sport that abides.

NOT SUCH A LONG WAY: The new rock stars of sports are the U.S.A. women’s soccer team. Since winning the Women’s World Cup in Canada, they have been fêted in celebrations and parades on both coasts. It would be easy to remark how far the team and the sport have come since the first women’s world soccer championship was won by the Americans in 1991, but the only real difference is in the attention they’ve received.

“We are linked,” said Carin Gabarra (formerly Jennings), the MVP of the 1991 tournament in China. “The game has changed, but mentally, we could compete today. We were tough. We have this fighting American mentality. It’s been that way since the ’80s.”

Gabarra graduated from UCSB in 1987 after scoring an NCAA-record 102 goals for the Gauchos. She returned in October of 1991 as a starter on the national team that defeated the UCSB women 10-0 in an exhibition match before departing to China.

In a semifinal match against favored Germany, Gabarra had a performance that foreshadowed Carli Lloyd’s sensational first half against Japan in this year’s final. The former Gaucho scored goals in the 10th, 22nd, and 33rd minutes, staking America to a 3-0 lead. She didn’t strike any goals from midfield, but she did hit a 25-yarder that would have made any highlight film. The final score was 5-2. Sound familiar? After defeating Norway 2-1 in the final, the U.S. players returned to their hometowns with hardly any hoopla.

Gabarra has been coach of the women’s soccer team at the U.S. Naval Academy since 1993. Her husband, Jim Gabarra, is coach of Sky Blue FC, a women’s professional team. Their three children have godmothers from the U.S. teams: Mia Hamm, Kristine Lilly, and Abby Wambach.

Carin voiced no complaints about the disparities in pay between women’s and men’s soccer. The U.S.A. women in 1991 received no compensation beyond travel expenses, which included flying coach and staying in budget lodgings. “I’d rather have less pay,” Gabarra said, “and be a world champion.”